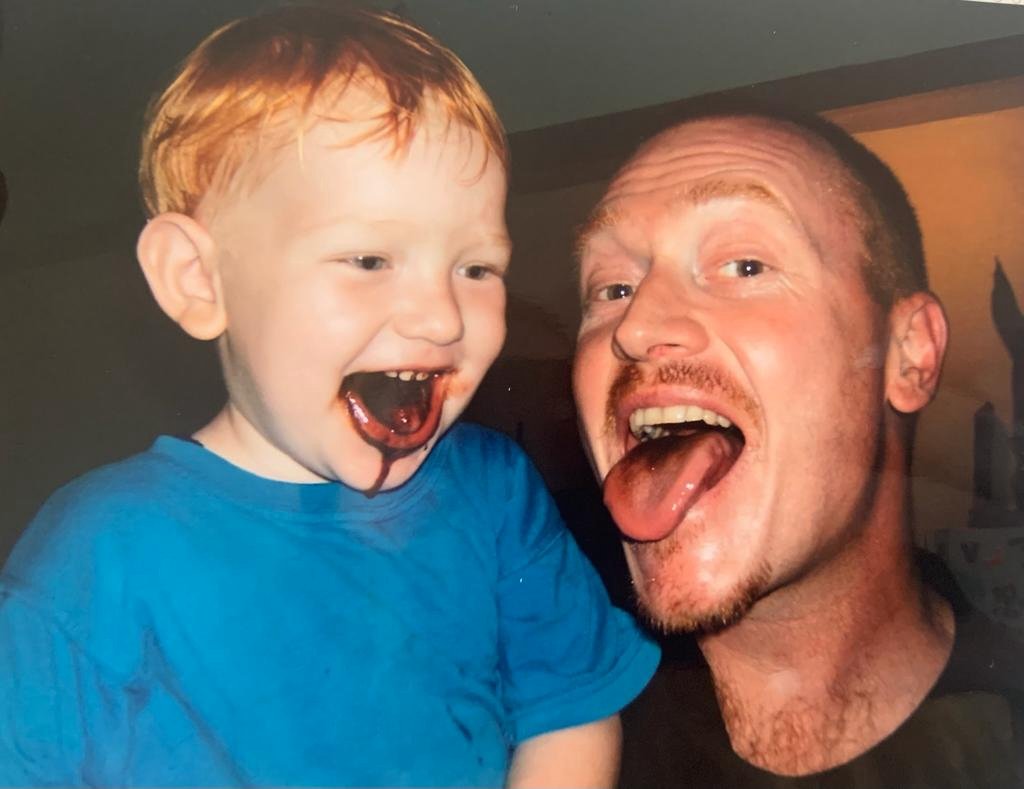

Kuan was our healthy and incredibly fit 18-year-old son, who was training passionately to fulfill his dream of playing college football in America. That dream, and our beautiful boy, were taken from us on Tuesday, 23rd August 2022, when he passed away very unexpectedly due to undiagnosed sepsis.

It was all so sudden. Kuan played football on the weekend. On Monday, he started feeling unwell, and by Wednesday he had a temperature, had started vomiting, and had diarrhea. We arrived at the Emergency Department in the early morning of Thursday but after spending seven and a half hours there, we were sent home with a diagnosis that he “just had a virus” and that we should give him Panadol and Nurofen and keep him hydrated. The reality is, that Kuan had bacterial pneumonia and was in the early stages of sepsis. Five days later, he was dead.

The defining day was the Thursday when we took him to the hospital. It was a day marred by an unimaginable series of hospital failures and poor judgments by medical professionals. The triage nurse told us Kuan was fighting an infection and was being categorised as “urgent”, but it was more than three and a half hours until he was even seen by a doctor. She examined him briefly and ordered a reactive protein test, a blood test, and a Covid test. We waited another three hours for the results. We were told the blood results simply showed a viral infection with no further treatment required. We left the hospital mid-afternoon, seven and half hours later, with the clear impression that this was not anything serious.

What emerged after Kuan’s death, was the extent of information that we were not told at the time. Information that was disclosed in the clinical governance investigation report months later, that we believe would almost certainly have saved Kuan’s life, had we been aware of it. The report told us that Kuan was triaged ‘Category 2’, which as per the Australasian Triage Scale, is given to people who need to have treatment within 10 minutes and have an imminently life-threatening condition. Had we been told this and understood what it meant; we would not have waited patiently for three and a half hours to be seen by a doctor. We have never received a satisfactory explanation for why this happened, other than there were an overwhelming number of patients present in the emergency department at the time.

The most concerning finding in the report was that when triaged, Kuan had clearly met the criteria for sepsis as per the New South Wales Health Adult Sepsis Pathway, with an onset of fever, cough, and breathlessness, including two ‘Yellow Zone’ criteria of an elevated heart rate of 137 bpm and a raised temperature of 39.2° C. This should have triggered an immediate response for the medical team to follow the sepsis pathway. It did not. The sepsis pathway stipulates that when a patient presents with two ‘Yellow Zone’ criteria including a new onset of signs and symptoms of infection, a blood gas is obtained to measure lactate, due to a lactate result of equal or above 2 (≥2) being a significant indicator with sepsis. A lactate level was not measured, and blood cultures were not collected. This would have saved his life. It was reported that workload pressures in the emergency department and false reassurance by the junior medical officer’s assessment of Kuan, led to him not having a senior medical review.

The report also confirmed that the doctor that eventually saw Kuan was an International Medical Graduate, who was on ‘Status 1 Supervision’. This meant she should have been under the full supervision of a senior doctor for every patient she examined. She saw Kuan alone, and the Senior Medical Officer on duty at the time, did not see Kuan at any stage. This International Medical Graduate decided to discharge Kuan, without understanding the results of the tests that were done on him. This explanation given in the report was that this junior doctor was placed in a position by the hospital where she was required to make decisions outside of her scope of practice, knowledge, and experience, as a result of not receiving the education, training, and supervision required for junior medical officers.

The c-reactive protein test she administered is a nonspecific blood test for a type of protein associated with inflammation in the body. Essentially it assessed the level of infection and inflammation within Kuan’s body. We now know that 8 to 10 mg/liter or lower is the normal range. Kuan’s result came back at 173ml/liter – 20 times the normal level. Yet, he was discharged with Panadol and Nurofen, just 44 mins after this result was confirmed. His discharge diagnosis was gastroenteritis presumed infectious.

What became evident from the investigation that was conducted on the hospital a few months later, was that 11 years after the New South Wales Health Adult Sepsis Pathway was introduced, it had still not been embedded in the routine practices of this hospital’s emergency department. In fact, the identification and management of sepsis was not mandatory in the junior doctor and international medical graduate orientation program for this hospital, and was the responsibility of individual medical staff to book in and attend. More disturbing was learning that this junior doctor did not even attend hospital orientation. This explains the report’s note that, “the level of appreciation and understanding of the signs of sepsis, in the context of a young person who looked well and reported feeling better following analgesia, led to best practice sepsis management not being commenced.”

We can blame the hospital and the medical professionals entirely. We believe we have good reasons to do that. The reality is though, we didn’t know anything about sepsis at the time. Of course, we are now very aware of the blatantly obvious symptoms, and it makes it harder to comprehend how medical professionals in an emergency department failed to act upon Kuan’s symptoms. What we have come to realise is, that relinquishing our responsibility as parents and relying entirely on health professionals was not necessarily the right thing to do. Had we been aware of the symptoms of sepsis at that time, there is no doubt our beautiful Kuan would still be with us. We believe that we all collectively failed Kuan. This is why we want to share Kuan’s story – none of the results were shared with us or explained to us at any point. Had they been, our lives today would have been very different.

Most of us come from cultures in which we go to hospitals expecting answers and to receive the level of care we need. The reality is, that most healthcare systems are failing to meet the needs of those they serve. They don’t have all the answers. We are not suggesting we all need to become knowledgeable in everything that has the potential to harm us. Instead, we believe it’s about creating a culture of mutual accountability. Our role in that is to be curious. Ask questions and continue to ask questions, until you are satisfied with the responses, and you receive the level of care you need. The other side of mutual accountability is medical services and health professionals adopting a duty of candour. An obligation to share every piece of information with patients and families and demonstrate complete transparency and vulnerability.